'Building my own eco house allowed me to combine my home and work space' – take a tour of this striking Passivhaus self-build

Built on a tricky sloping site in Yorkshire, this timber-clad home with its adjoining weaving studio is a masterclass in Passivhaus design

After having looked after her elderly and infirm parents for many years, retired architect, Susi, was looking for a fresh start. Her current home wasn’t suitable for a renovation or remodel, so she decided to search for a site on which to build a new house.

“I wanted a home that was sustainable, comfortable and would look after me,” says Susi. The design therefore would need to be considerate of any future life changes which might impact Susi in the years to come.

Another huge want of Susi's was for her new home to achieve Passivhaus standards. A highly prized accolade, which would require an architect who was well-versed in designing to this standard.

Finding the perfect plot

“When I mentioned to some close friends that I wanted to do a self-build with space for a weaving studio, they told me they were interested in buying a property with existing planning permission for an ‘eco’ home on the site. So we entered into a parallel purchase.

"They bought the house, which I rented for the duration of the building programme, and then I bought the site from them. We all exchanged contracts and completed at the same time.”

The sloping site has views across rolling countryside, which Susi wanted to maximise without impacting on her neighbours' views. This was particularly important to her as the original design that had been granted planning permission had blocked these, but had been passed at appeal.

To overcome this, Susi, along with her friend and fellow retired architect, Marc Medland, designed a house where the roofline sits at the ground level of the neighbouring building.

“As the site already had permission for a house, there were no planning issues at all and the new proposal was welcomed by the neighbours,” she says.

The charred Siberian Larch used for the exterior is insect resistant and is less likely to fade and weather in the way stained timber does. It also contrasts with the sandstone spine of the house

The vibrant orange front doors stands out against the dark timber cladding

The houses appears to be a single-storey design from the front

The original plot

The house build in progress

Achieving Passivhaus standards

The duo designed the two-storey house – with an adjacent single-storey studio – taking it to the planning permission stage. “We saw the sloping site as a positive feature in that it gives the house environmental shelter and privacy and provides robust thermal protection,” says Susi. “Although the neighbours are quite close, it feels private and sits modestly into the hillside.”

Through her teaching at Sheffield University School of Architecture, Susi was familiar with HEM Architects and knew of their expertise in Passivhaus home design. She contacted director Paul Testa at an early stage before submitting the planning application to ensure that the design would be feasible for Passivhaus certification.

Following planning approval, she appointed them and JAM Structural Design to complete the project. “I was very much aware that the self-build project management was their remit and that something of this complexity was more than I would be able to commit to.”

The rooms in the house are light and bright and make the most of the views out over the fields

The first floor spaces also make the most of the countryside views

The main bedroom has floor-to-ceiling glazing

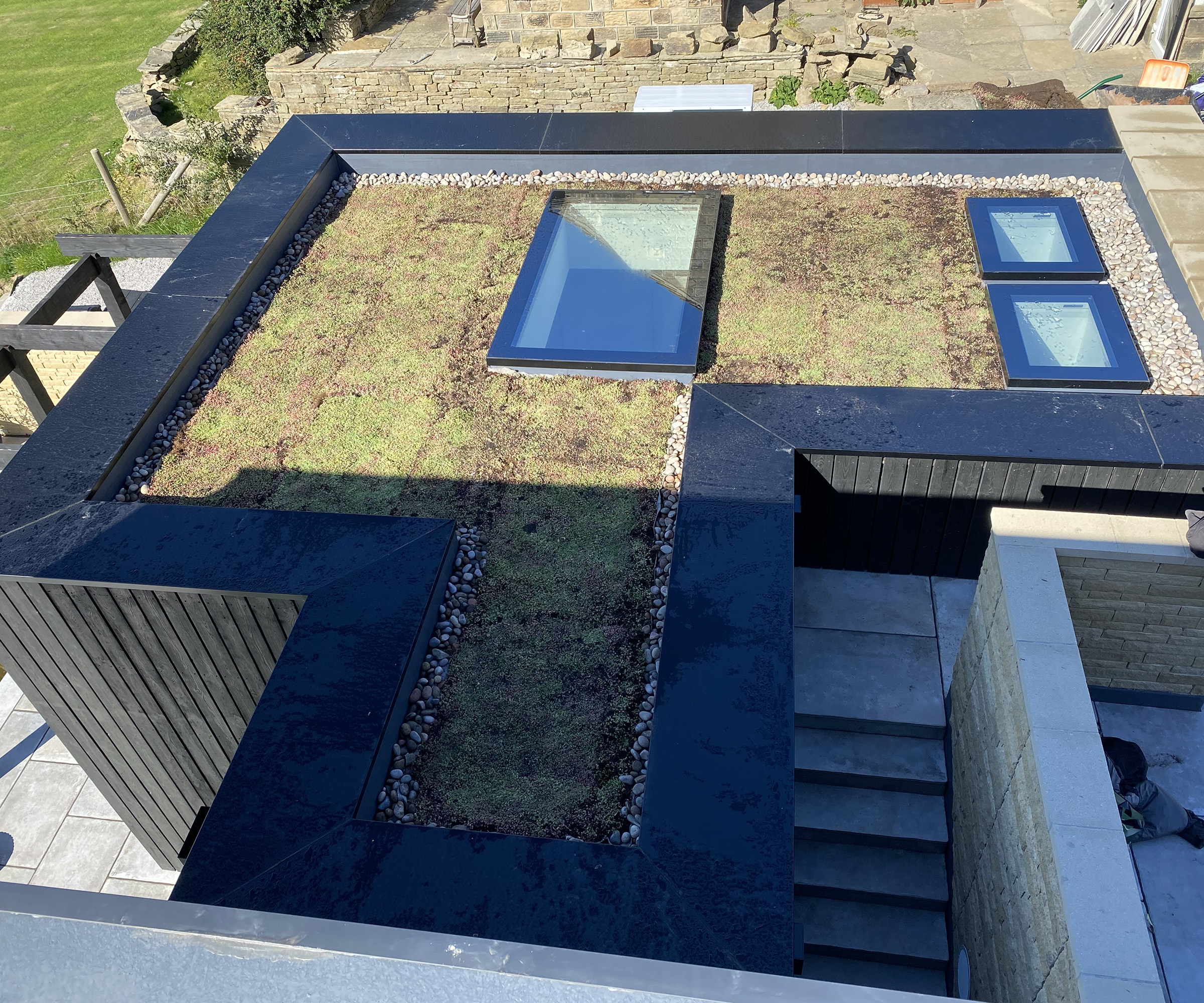

A sedum roof further boosts the eco credentials of the house

Planning for the future

For Susi, it was essential that her eco house could be adapted to deal with any potential life changes such as diminishing mobility or care needs, so movement around the building is generous and gentle.

“The openings are wide as are the internal and external stairs, and the thresholds are level,” she says. “There is also an allocated area on the first floor that could take a lift, should it ever be required.”

The stone for the spine wall was sourced locally and was chosen to reference the dry stone walls that are so prominent in the area. Other raw materials include the precast concrete external walls, which are visible in the lower rooms of the house and in the studio, and the floors are a sealed concrete screed.

“I wanted the house to feel comfortable and welcoming so the finishes and colour are natural and warm,” says Susi.

Visually, the spine wall ties the building to the ground and breaks the south façade. It also acts as a support for the stair and the floor and roof structure

The house has been futureproofed with wider doorways and level thresholds

The kitchen diner occupies one side of the house

Standout features

From the driveway, the house appears as an unassuming single-storey black box, but while modest in scale it is generous spatially. The main entrance is at first-floor level where there are two bedrooms, one of which is a multifunctional space. “It can also be used as a place to exhibit my work,” explains Susi.

The timber cladding is Siberian larch, which is charred using the process known as shou sugi ban. The house has been named Sort Trae, which means ‘Black Wood’ in Danish and is a reference to the Viking roots of the area.

Stairs lead down to the ground floor where the space opens up to reveal a large kitchen and dining area with a living area and study on the other side of a handcrafted sandstone spine that forms the centrepiece of the house.

From the first-floor entrance, stairs lead down to the main living spaces

Susi's work studio sits alongside the main house

Due to the sloping site, the rear of the house is two storeys

Controlling the interior temperature

Thanks to the considered design, every room in the house reveals expansive valley views while being protected from the weather by the building’s high-performance envelope – the mass of the building absorbs and holds the heat, emitting it in the evening.

Triple-glazed windows and rooflights as well as deep reveals help to balance summer heat gain and winter losses. “The air test achieved an air change of 0.54 ACH (air changes per hour), which is well within the 0.6 ACH required to meet the Passivhaus Standard, ” says architect Paul Testa.

Overheating is reduced by means of internal blinds in the upper rooms and the house is naturally cross-ventilated. “The stairwell acts as a vertical stack, which pulls cool air up through the house to the north elevation and through the upper rooms,” Susi explains.

Susi designed the kitchen as a functional workplace with views out over the garden

The split-level living room is on the opposite side of the stairwell to the kitchen

Tackling the weather conditions

“The site is exceptionally windy, so overheating has not proved to be an issue so far. During winter, when the external temperature is below freezing, but the sun is shining, the solar gain means that the internal temperature can reach 20 degrees with no heating.”

Both the house and studio successfully fulfilled the requirements for Passivhaus airtightness standards. “This was critical from the very start of the project and the builder pre-tested the building for any potential leaks before it was tested officially,” says Susi.

It wasn’t practical to have a balcony due to the windy exposure of the site, but Susi wanted to be able to open up the first floor to sit and enjoy a coffee and to read. As a compromise, the window aligned with the top of the stairs opens fully with glass balustrade

Obstacles along the way

The project ran fairly smoothly, considering it was carried out during Covid restrictions, with the only main delay at the beginning during the groundworks. “I was aware that lead times were likely to be longer than usual and made decisions regarding the procurement of materials in good time,” Susi explains.

“It was a wet and stormy winter, though, and this interrupted some of the work. On Boxing Day there was a gale-force wind and I found myself chasing slabs of insulation the size of mattresses down the driveway. Only when I’d finally managed to tie them down could I laugh about it!”

Another element of the house that proved somewhat of a challenge was the suspended precast concrete stair that is situated between the house and the weaving studio. Part of it forms a section of roof to the studio so it needed to be insulated and watertight as well as have Passivhaus ventilation.

“When it was being installed, by crane, it swung alarmingly over the roof of the neighbouring garage, but thankfully it slotted into space without a problem.”

Susi Clark's weaving studio was designed to accommodate a large floor loom and several smaller looms, used for her own work and teaching workshops

Strategic rooflights provide excellent daylight and the bifold doors connect the room to the garden

“I would never change the experience of building my own home,” says Susi, adamantly. “It’s comfortable, hospitable, calm and beautiful – and it has my physical and mental wellbeing at its heart.”

If you're interested in building a similar project, our guide to what it's like to live in a Passivhaus home has some great insights on what to expect if you go down this route.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.