Heating: Beginner’s Guide

Choosing a heating system for your self build or renovation project is a key decision, but where do you start? We explain all in this in-depth guide

Choosing a heating system for your self build or renovation project will present a number of options, and will be one of the most important decisions you make.

Not only is this going to affect your experience of living in the house, but will also determine the running costs of your home.

The starting point for any heating system design is two-fold. You will need to calculate how much heat is needed in the first instance, which will mean getting a detailed calculation carried out by a properly qualified heating engineer.

In addition, you will need to choose your emitter right at the beginning of the process as that decision will also affect everything else.

Choosing a Heating Emitter

The three main options for heating emitters are:

- Underfloor heating: This tends to be the emitter of choice for many self builders and extenders, for the comfort, efficiency and the extra wall space it gives

- Radiators: Radiators are cheaper than UFH and choice is as much about aesthetics as it is by the amount of heat needed

- Skirting board heaters: These have a lot to offer, especially in retrofit projects, and are something of a halfway-house between UFH and radiators

How Does a Basic Heating System Work?

At its simplest level, think of a heating system in two parts: the bit that generates the heat, and the bit that distributes that heat around your home, for instance heating a kitchen or heating a conservatory.

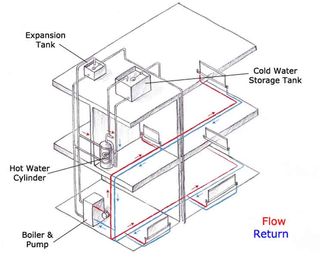

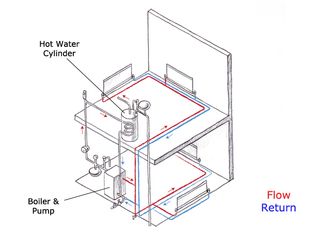

You should also, at this early stage, understand that heat is required in two forms — for space heating (i.e. keeping you warm) and for hot water (i.e. for showers etc). So, the simplest of all systems would have:

- a boiler (choosing a new boiler to power to heat up water and incorporates a pump to move it around)

- piping (to move that warm water around your house)

- emitters (choosing an emitter to be radiators or underfloor heating)

- hot water cylinder (hot water storage for use as required, although these are not required with a ‘combi’ boiler — more on which later).

(MORE: Underfloor Heating or Radiators? Choosing Emitters)

How to Choose a Heat Source

The big decision is whether to go with just a boiler or go down the route of installing a renewable energy system, and if so, whether it will be the sole heat source.

A gas boiler supplemented by solar thermal panels or an air source heat pump are becoming increasingly popular options thanks in part to increases in the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI — the government’s scheme to incentivise the take-up of renewable heat-generating technology).

In situations where there is a very high heat demand in older houses, wood pellet boilers are still a good option. Although, bear in mind the RHI tariff is not as generous as it was.

The reality remains that if mains gas is available it is difficult to ignore. But beyond that, all options are available, and the best and perhaps only way to make the right decision is to start with the heat requirement and all the other factors individually rather than considering a heating system as a single entity.

How to Control a Heating System

The control system will be largely dictated by the system being installed.

To make a difference to your heating bill, the control system must allow the temperature to be set for each room. It is uncommon that a house will need every room to be heated to the same temperature at the same time (think guest bedrooms which only receive occasional use).

Also, as daft as it sounds, you will need to understand how your system works in order to control it effectively, especially with a more complex system.

You could have UFH on the ground floor and radiators in the bedrooms; there could be more than one heat source with a boiler supplemented with solar panels; and there are ‘intelligent’ systems that apparently learn when we want the house heated and to what temperature.

The control system is as important as the heating system itself and without knowing how to operate the system it is not possible to gain the full benefit of the investment.

Hot Water Cylinders Explained

Combi boilers are the only option that do not require a hot water store. That apart, there are a number of other reasons for choosing another option (which include a hot water store) — not least, the increased efficiency of all the other options and that combi boilers preclude the use of any form of renewable energy.

The volume of the cylinder will be determined by a calculation which takes into account the space heating requirement of the house, the number of bathrooms and the number of people in the house.

The decision is then for a vented or unvented cylinder.

Vented cylinders do not maintain any pressure so ensuring good pressure at the tap or shower relies on something else, typically a header tank in the loft or a pump.

You’ll have a copper cylinder in your airing cupboard and an expansion tank in the loft, as well as a cold water storage tank.

Unvented cylinders, which include thermal stores, do maintain pressure and deliver water to the outlet at mains pressure. But they come with a higher price tag and an annual maintenance bill.

You’ll have a white cylinder in your airing cupboard and nothing in your loft.

A thermal store will also maintain water at layers of different temperatures (called stratification) which is useful for multiple heat sources and the requirements of different outlet types (i.e. UFH and hot water).

You’ll generally be guided (or told) by your supplier or installer what cylinder to install. The advice would be to do some research and take part in the decision – there is a fairly wide spread in terms of efficiency and price.

What Size Boiler Do I Need?

Boilers come in different sizes (measured in kW) and you need to specify the right one — a boiler that’s too large will not only be more expensive but will operate less efficiently than an adequately sized model.

Bear in mind that plumbers will be more likely to oversize as they don’t want callbacks from problems relating to a small model, and the capital cost is passed on to you anyway. Many of the boiler suppliers offer online guides for choosing the right size.

You can have a stab yourself by adding up the required heat output from the radiators or underfloor heating system (taking into account room sizes, insulation levels and window sizes; this can usually be calculated on radiator company websites) then adding 3kW for hot water and a 10% buffer.

Typical boiler requirements for a larger detached house would be in the region of 30kW.

Heating System Jargon Buster

Because water expands when it heats up, there needs to be room in the heating system to accommodate the additional capacity. In traditional systems this would be in the form of an expansion tank in the loft, but on more modern systems is in the form of an expansion vessel, located either next to or within the boiler or hot water cylinder.

The storage vessel which supplies hot water on demand to taps and showers, located in the airing cupboard. Depending on the type of system, it either heats up cold water supplied by the cold water storage tank, stores hot water supplied directly by the boiler, or heats up cold water supplied directly from the mains.

A boiler is a vessel that transfers energy (usually either gas, oil or LPG) into heat to warm up water. The amount of heat it can produce is measured in kW, and typically boilers range in size from 15 to 40kW for domestic applications. It usually incorporates a pump to feed the water through pipes to the radiators.

Heating Fuel Options: Cost Comparisons

To begin, there are no good economical reasons for using electricity for heating purposes, unless all the electricity being used is produced on site from a renewable energy source. Equally, LPG does not make a lot of sense. A litre will cost around 47p (according to Which?) and will deliver about 7kWh of heat, or about 6.7p/kWh. Heating oil is now about the same price per litre and will deliver about 10kWh, or about 4.8p/kWh.

Mains gas (when available) is the cheapest fossil fuel option in terms of installation, capital and running costs. Renewable energy systems still have a relatively high capital cost but their low running cost make them the better long-term option.

To compare the cost of fuel options, we take a look at the capital costs of various types alongside the annual running costs and how this will stack up over the years, below (based on an annual heat requirement of 15,000kWh/yr of a typical house.

| Fuel | Capital Cost* | Fuel Price (per kWh)** | Annual Running Cost | RHI Income | Fuel Cost Over 7 Years | Total Cost Over 7 Years | Fuel Cost Over 10 Years | Total Cost Over 10 Years*** |

| Mains Gas | £2,500 | £0.06 | £850.50 | N/A | £8,576 | £11,076 | £14,916 | £10,916 |

| Oil | £5,000 | £0.04 | £630 | N/A | £6,886 | £11,886 | £12,544 | £22,544 |

| LPG | £4,000 | £0.07 | £1,102.50 | N/A | £12,045 | £16,045 | £21,942 | £29,942 |

| ASHP | £7,500 | £0.15 | £750 | £1,049 | £7,566 | £7,723 | £13,161 | £13,318 |

| GSHP | £12,000 | £0.15 | £562.50 | £2,031 | £5,670 | £3,453 | £9,862 | £7,645 |

| Biomass | £15,000 | £0.06 | £866.25 | £1,011 | £6,839 | £14,762 | £10,397 | £18,320 |

* Capital cost includes installation and ancillary equipment

** Fuel cost includes inflation at 12% for electricity, gas, LPG and oil and 4% for biomass

*** 10 year cost includes replacement boilers for gas, LPG and oil

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

Tim is an expert in sustainable building methods and energy efficiency in residential homes and writes on the subject for magazines and national newspapers. He is the author of The Sustainable Building Bible, Simply Sustainable Homes and Anaerobic Digestion - Making Biogas - Making Energy: The Earthscan Expert Guide.

His interest in renewable energy and sustainability was first inspired by visits to the Royal Festival Hall heat pump and the Edmonton heat-from-waste projects. In 1979

this initial burst of enthusiasm lead to him trying (and failing) to build a biogas digester to convert pig manure into fuel, at a Kent oast-house, his first conversion project.

Moving in 2002 to a small-holding in South Wales, providing as it did access to a wider range of natural resources, fanned his enthusiasm for sustainability. He went on to install renewable technology at the property, including biomass boiler and wind turbine.

He formally ran energy efficiency consultancy WeatherWorks and was a speaker and expert at the Homebuilding & Renovating Shows across the country.