How to choose a heat pump: The different types of heat pump explained

Heat pumps require specialist installation and expertise to get right — this introductory guide explains what you need to know

Heat pumps may be an established as the go-to solution for those off mains gas looking for a renewable alternative to oil or LPG, but they are now heralded as a low-carbon alternative to main gas boilers.

Heat pumps simply move heat from one place to another. They absorb heat from the air, ground or water, extract the heat absorbed, and then pass it over a heat exchanger which transfers the heat to air or water, which in turn heats the house. We all own a heat pump in our home already, in the shape of a fridge.

As a general rule, heat pumps work best when flow/return temperatures are lower than the 60-70°C range required for older radiators and, of course, hot water. As such, heat pumps are best paired with lower temperature emitters such as large radiators or underfloor heating.

If you're thinking of installing a heat pump in your home, then there is a lot to consider and specialist advice to be sought to ensure you choose the right type of heat pump for your home. This beginner's guide will answer your key heat pump questions and more.

How to choose a heat pump

The different types of heat pump

There are three types of heat pump available:

- Ground source heat pumps whereby pipes extract latent heat from below the ground (either in trench-based ‘slinkies’ or more expensive boreholes).

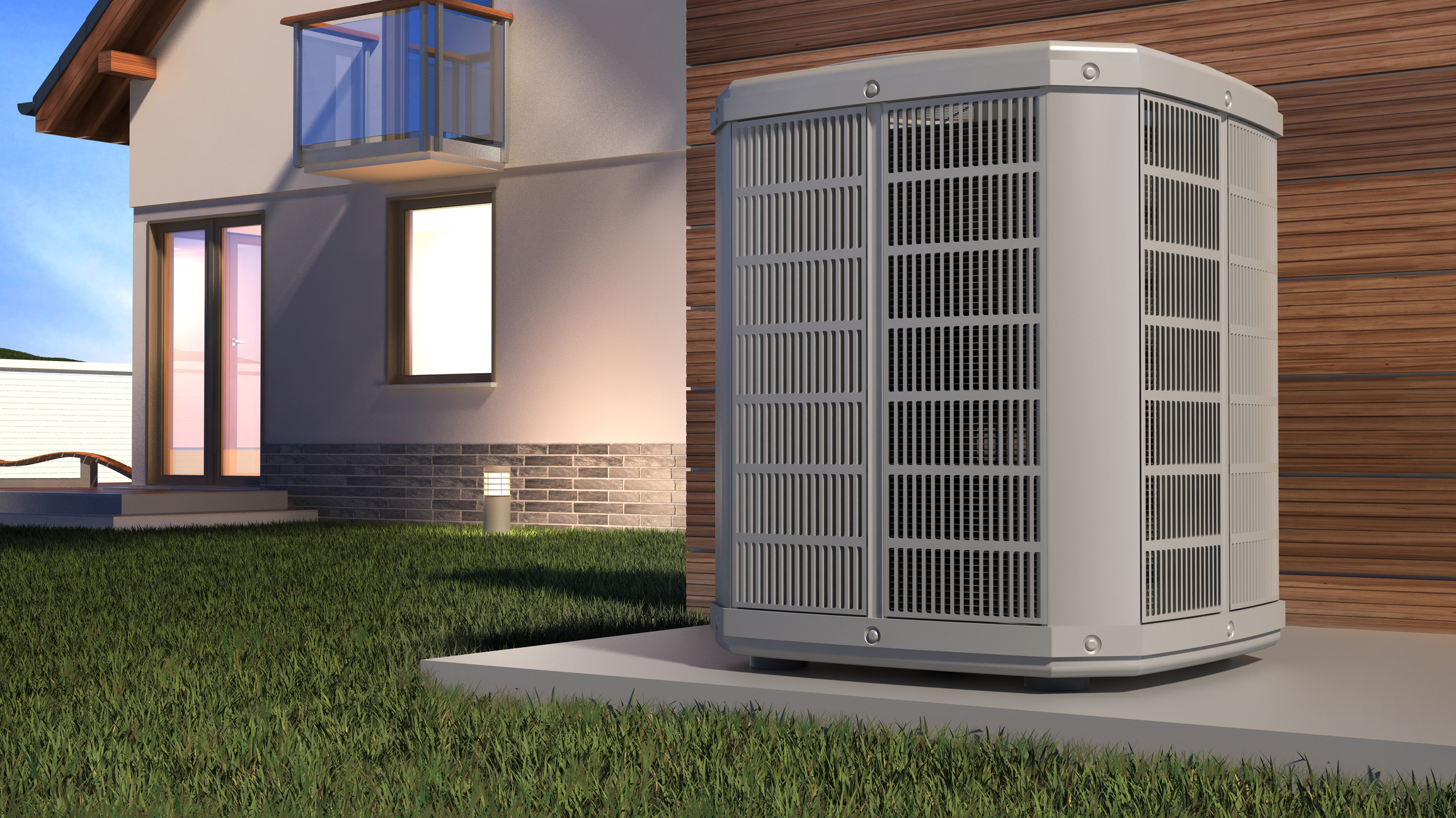

- With an air-source heat pumps, a unit similar in look to an external air conditioning kit extracts heat from the air and runs it through a heat exchanger.

- Water source heat pumps extracts heat from a body of water such as a lake, and is less common option for UK homes.

How do air source heat pumps and ground source heat pumps compare?

There are a number of key differences to note between air source heat pumps and ground source heat pumps, including:

Efficiency

A typical claimed SCOP figure for an air source heat pump might be 3.2; the comparable figure for ground source heat pumps is more like 4, so for every 1kW of electricity, 4kW is generated.

Thus ground source heat pumps appear to be slightly more efficient but as the compressor and the refrigerant is very similar in both systems you really have to check the real temperature of the heat source, namely the ground and the air.

Towards the end of the heating season (January onwards) the ground could be colder as the heat is extracted. If the air temperature is therefore warmer than the ground temperature then it can be argued that the ASHP could be more efficient. Ground conditions and geographical location are crucial when making this choice.

Installation

Ground source heat pumps require a large garden or piece of land to be installed, or are installed in deep boreholes. Both types of installation result in excavation costs. Air source heat pumps are not installed in this way. Instead the external condenser unit sits in a box on the outside wall and so is cheaper to install.

Incentives

The Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) used to offer a more generous return for owners of domestic ground source heat pumps before its closure this year. The Boiler Upgrade Scheme, which replaced in the RHI in spring, offers £6,000 for those installing GSHPs and £5,000 to homeowners installing ASHPs.

The higher incentive for homeowners installing GSHPs reflects the higher capital and installation costs of this technology.

How efficient are heat pumps?

The performance of the heat pump after installation will be expressed as a Seasonal Coefficient of Performance (SCOP). The SCOP of heat pump is usually around 3-4, but there is possibility of it being slightly lower or higher. What a SCOP of 3 or 4 means is that for every 1kW of electricity which is put into the system, 3 or 4kW of heat will be created.

This number is a factor not just of the kit but of the specific design — for instance, will you be choosing underfloor heating as an emitter, and will you be using a heat pump to heat both the house and the hot water.

Typically, air source heat pumps would expect to enjoy a SCOP of around 3.2 (i.e. 1kW of electricity creates 3.2kW of heat) and ground source heat pump more like 4.

Why is it important to size heat pumps properly?

Unlike gas boilers, getting the size of a heat pump right is critical. An oversized heat pump is outputting more heat it needs to operate for a shorter period of time to reach the desired temperature — this is called short-cycling.

An undersized heat pump will be working at its maximum, and least efficient, output for most of its operational time.

It needs a specialist heat pump installer, backed-up with good manufacturer software, to get the calculation right.

Are inverter heat pumps better?

Until relatively recently non-inverter heat pumps were the norm. They operate by being either on or off. Inverter heat pumps, however, act more gradually, increasing or decreasing output to meet the prevailing conditions and demand.

Each time a heat pump starts up it consumes energy in balancing the pressure in the system and bringing the refrigerant to the right temperature before the heating process can start.

An inverter heat pump can operate 24/7, never or seldom switching off, eliminating the losses caused by stopping and starting.

These pumps, which are also called modulating heat pumps, vary the speed at which the compressor operates to vary the heat output.

A house with a heat load of 20,000kWh would have a peak load of 14kW, so we need a 14kW heat pump. That peak heat load is calculated to deal with an outside air temperature of (usually) -2˚C. Obviously, it is not always -2˚C outside so we do not always need 14kW. An inverter, or modulating, heat pump varies the heat output to suit prevailing conditions, saving electricity and improving efficiency.

A continuous 24/7 operation may seem odd to those of us used to being in control of the boiler, but some manufacturers are claiming up to 30% reduction in running costs by using this method.

What is a hybrid heat pump?

A hybrid heat pump or bivalent heat pump is one with two heat sources — a heat pump and a conventional boiler, for example. As such, a hybrid heat pump system is efficient because it selects a different fuel as and when the efficiency or heat demand changes. As an example:

- an air source heat pump that operates in spring, summer and autumn, when the weather is mild (highest efficiency)

- and a conventional boiler that operates in winter (at good efficiency)

Heat pumps now have weather compensation as standard and so can be programmed to shut down when the outside temperature drops below 7°C (when it starts to get inefficient), and allow the gas or oil boiler to kick-in.

What type of heat pump should I choose?

Used in the right way, in the right place, air source heat pumps provide a good, viable and cost-effective option. Many of the newer models are much quieter than earlier models, which had a reputation for being noisy.

Ground source heat pumps are expensive to install but they offer the lowest running cost of any renewable energy. Systems are generally reliable and long-lasting.

A good, qualified, experienced installer will ensure the ground source system is designed to properly meet the ground conditions, and the demands of the house, and will run happily for 20 to 30 years.

Follow our 5 point checklist to find out the answer to is my home suitable for a heat pump, or if you've got an older home, we ask the experts, are heat pumps suitable for old homes.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

Tim is an expert in sustainable building methods and energy efficiency in residential homes and writes on the subject for magazines and national newspapers. He is the author of The Sustainable Building Bible, Simply Sustainable Homes and Anaerobic Digestion - Making Biogas - Making Energy: The Earthscan Expert Guide.

His interest in renewable energy and sustainability was first inspired by visits to the Royal Festival Hall heat pump and the Edmonton heat-from-waste projects. In 1979

this initial burst of enthusiasm lead to him trying (and failing) to build a biogas digester to convert pig manure into fuel, at a Kent oast-house, his first conversion project.

Moving in 2002 to a small-holding in South Wales, providing as it did access to a wider range of natural resources, fanned his enthusiasm for sustainability. He went on to install renewable technology at the property, including biomass boiler and wind turbine.

He formally ran energy efficiency consultancy WeatherWorks and was a speaker and expert at the Homebuilding & Renovating Shows across the country.