Choosing foundations for difficult sites: Expert advice for getting them right

Choosing foundations for difficult sites can lead to rising costs, delays and long-term problems if you get them wrong. Here's how to get them right

Choosing foundations for difficult sites and picking the wrong ones can lead to various issues such as spiralling costs, delays on site and even a situation where subsidence might occur, threatening the long term viability of the project itself.

Knowing which foundation systems and soil type go together is a good start, but if you're also faced with sloping sites, the close proximity and/or presence of trees, and ‘bad ground’, what can appear a viable project can suddenly feel like a daring gamble.

With the primary role of foundations being to anchor the building to good bearing ground (in other words, ground capable of supporting the building), even relatively lightweight structures, such as timber frame houses, need to be securely ‘fixed in place’ to resist ground movement.

So if this is your current predicament, what can you do to turn a problem site into something more manageable and what are the rules when it comes to choosing foundations for difficult sites?

Foundations for difficult sites require a structural engineer and an experienced build team

"Perhaps the most important aspect when designing and constructing a foundation, is the mandatory involvement of a competent structural engineer who has experience of working on similar sites, with a proven record of success," says architect, Ninian McQueen.

"Any proposed structures must be able to withstand and exploit the character of a specific site. Therefore, it is prudent to engage a local structural engineer, as their pre-existing knowledge of the site will provide a head start when it comes to designing foundations for difficult sites.

"This also applies to the rest of your design team," states Ninian, "and the contractors you eventually decide to work with. Select them based on the relevant experience they have, not just their fee proposals."

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

Ninian MacQueen is an ARB registered, and RIBA chartered, architect. He studied at the Mackintosh School of Architecture in Glasgow, before completing his ‘Part 3’ at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. He worked for four Stirling Prize winners – including Richard Rogers, Norman Foster and AHMM architects – as well as smaller firms, before starting his own private practice: Borderland Studio.

What are difficult sites?

If you're searching on Plotfinder for your next project, you may be wondering what exactly constitutes a difficult site. Is it obvious, or could you be missing something more subtle that will mean suddenly you are faced with having to find extra funding when it comes to choosing foundations for difficult sites?

Sloping sites

Although it's easy to assume only steep slopes cause issues, even quite shallow slopes can pose complications too and lead to you needing foundations for difficult sites.

As a rule, when it comes to knowing how to build on a sloping site, the steeper the site the greater the cost, with expensive retaining walls often required on gradients of more than 1:25, to hold back the ground.

However, designing the drainage systems and access will also need careful attention, and surface water coming down the hill will need to be channelled around the building.

The biggest decision, says Ninian McQueen is where to position the building.

"As an architect, it's important we take into account the nature of the site when coming up with architectural proposals. The foundation should be appropriate for the needs of the brief, and work in harmony with the building itself.

"Does the client want something that sits gently on the ground? Or would they prefer something that looks and feels ‘heavier’ or ‘dug into the ground?' are all questions we need to ask," he explains.

One option is to build into the hill, excavating to create a level base. Alternatively you might decide to extend the building outwards with supporting walls constructed under the raised area. Both options are likely to add upwards of £5,000 to your groundwork costs.

The compromise method is to fit the house to the slope with a series of steps creating a split-level layout. This will reduce the amount of excavation, although it can still add as much as 10 per cent to your overall build cost. However, sloping sites can provide an opportunity for adding extra space by incorporating a basement as a cost-effective way to fill the void when building out above ground level.

Sites with trees

Retaining mature trees can add a lot to the ‘amenity value’ of a property, while helping to mollify planners and disgruntled neighbours. The problem is, notoriously thirsty species such as willows and poplars can cause ground instability in subsoils such as shrinkable clay meaning you'll have no choice but to consider foundations for difficult sites.

As a rough guide, if you're building by trees, it is recommended that buildings on conventional foundations should not be closer to single trees than the height of the tree at maturity, or one-and-a-half times for groups of trees; the National House Building Council(NHBC) publishes tables showing ‘safe distances’. To determine foundation depths, you also need to consider the shrinkability of the subsoil and the water demand of the species, as well as noting the distance of trees from foundations.

Cutting down trees can also cause problems. For several years following the clearing of a site, clay soils can gradually expand, absorbing the moisture no longer taken by the trees. The foundation design needs to allow for this.

Soil on your plot

Water content in soil is important to assess as water movement could potential cause subsidence issues if the wrong type of foundation is chosen, meanwhile if the soil is totally waterlogged this can also affect which foundation might be suitable.

If you're visiting a site and looking for signs of issues with the soil, springy or boggy ground is indicative of a high water table where soil can expand when frozen. However, surface groundwater rarely freezes at depths of more than half a metre. Subsequently, the new foundation needs to be deep enough to prevent the effect of any upward movement or ‘frost heave’ in the ground.

If you're looking at a site with clay, it's also important to note that shrinkable clays suffer seasonal volume changes, although this rarely extends more than a metre below the surface. Problems are exacerbated by trees and shrubs in close proximity, combined with periods of drought and heavy rainfall.

Regardless of the type of soil, what you will need to establish is the bearing capacity of the soil.

Choosing foundations for difficult sites

As well as looking at the gradient of the ground, the soil type and the amount of trees within the vicinity of your site there are also a number of other factors to take into account.

Previous use of the site

Previously developed ‘brownfield’ land can contain all manner of horrors, such as old footings, drains and wells. Former industrial uses or dumps may also harbour potential risks with toxic chemicals or methane gas, so it’s advisable to consult local authority registers of contaminated land. In some cases, however, the solution can be relatively simple such as specifying sulphur-resistant cement.

Past excavation or mining activity may also have made the ground highly unstable, with new foundations potentially subject to periodic, unpredictable subsidence that could leave you researching how much does underpinning cost.

Site access

"How difficult it is to get to the site of a proposed building project can be a big impediment to its relative success," says Ninian.

"A small site at the end of a very narrow and long path in the countryside or in a very tight urban location can cause all manner of problems. Getting large quantities of building material and any associated machinery into, or close enough to, the site can be very tricky.

"The sequence of events required to install the foundation and complete the overall construction can also be severely limited in such situations," he warns. "A careful plan must be drawn up before any work on site is started to ensure the processes involved are viable."

Budget

"How much money the client has to spend on their project will also affect the viability of building foundations on a tricky site," says Ninian McQueen.

"The more complicated the type of foundation that is required, the more its installation will cost. This is because more raw material, more time on site and more skilled, or specialised, contractors are required to carry out the work."

Foundations for sloping sites

From an architectural point of view, foundations for difficult sites involving slopes, "depends on the design intent for the building, and if the ground floor level of the new building is intended to align with the highest point of the slope or if the floor level will align with the lowest point of the slope," says Ninian.

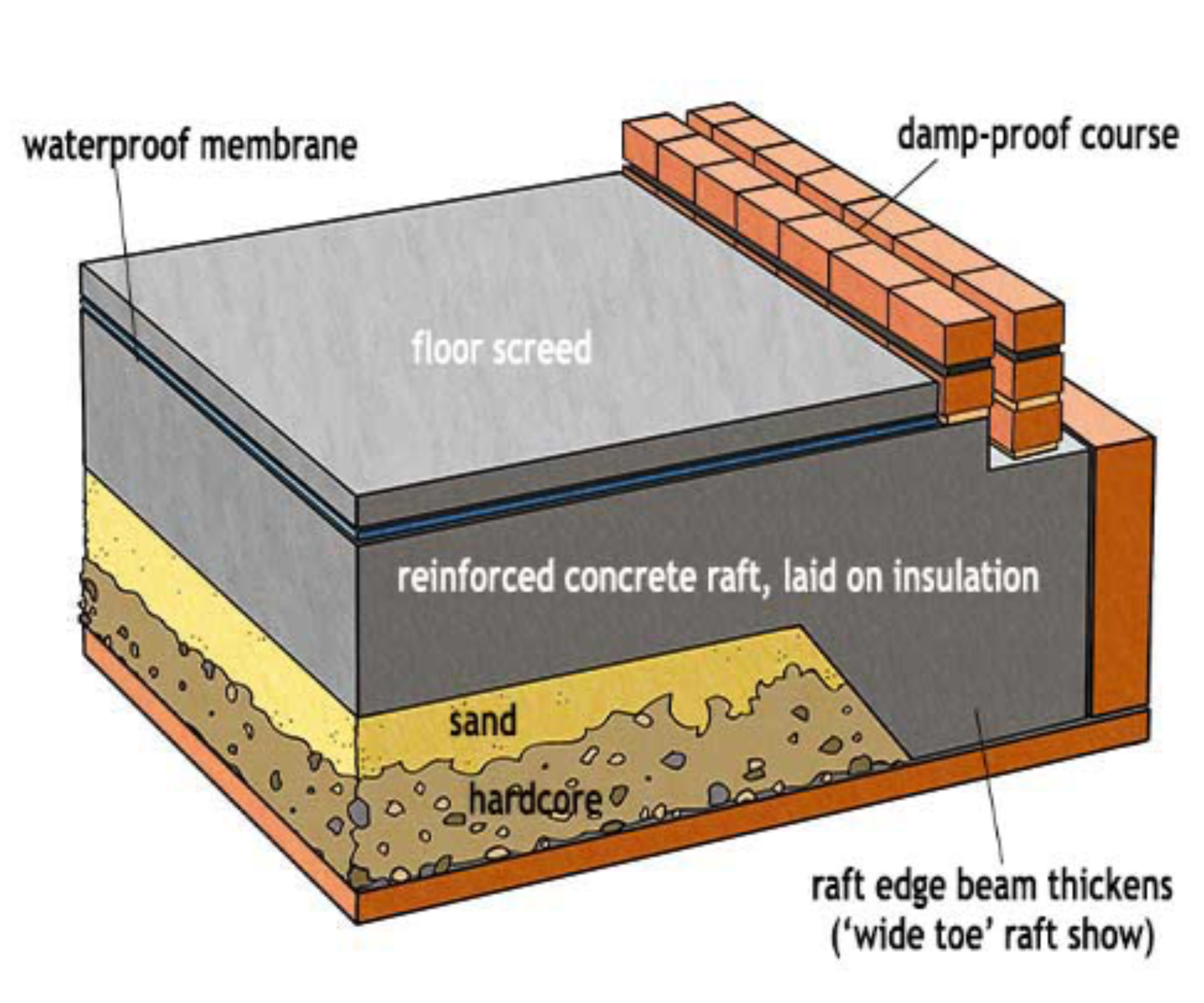

"Depending on the proposed floor level - and the amount of excavation that is considered viable - then either a flat raft foundation, (the alternative ‘wide toe’ design is used on ground with poor compressibility), or a series of concrete beams, or strip foundations, at different heights can be utilised. A stepped slab (instead of a flat one) could also be utilised to reduce the amount of excavation required."

However, don't assume a slope is always disadvantageous, says Ninian.

"Placing a building into a newly excavated niche towards the base of a slope has its advantages; for example it can utilise the thermal mass of the surrounding soil, as well as produce a finished building with a much smaller visual impact on its surroundings.

"The main disadvantage of this method is that digging can be time consuming and therefore expensive - hefty retaining wall structures with suitable drainage systems are also required.

"An option to consider - if the client requires a floor level at the top of the slope," suggest Ninian, "is to essentially form a platform propped up above the ground on stilts that have been piled into the ground."

Foundations for sites with trees

"If a proposed building site is located somewhere close to protected trees such as those with ‘tree protection orders’ in an urban area, or close to woodlands or other natural habitats," says Ninian, "in this situation it is common to encounter ‘tree root protection areas’, which often become an issue when seeking planning permission.

"Root barriers can also be a useful method of protecting foundations," adds Ninian. This involves excavating a narrow trench between the tree and the building about a metre deeper than the lowest roots (trenches are typically about 4m deep) into which large rigid plastic sheets about 4mm thick are inserted.

"However, planning conditions may stipulate that certain foundation types are not permitted due to the potential damage they can cause neighbouring trees. Careful surveying and the implementation of helical micro-piles is often the answer, as they can be deployed carefully so as to avoid damage to tree roots entirely.

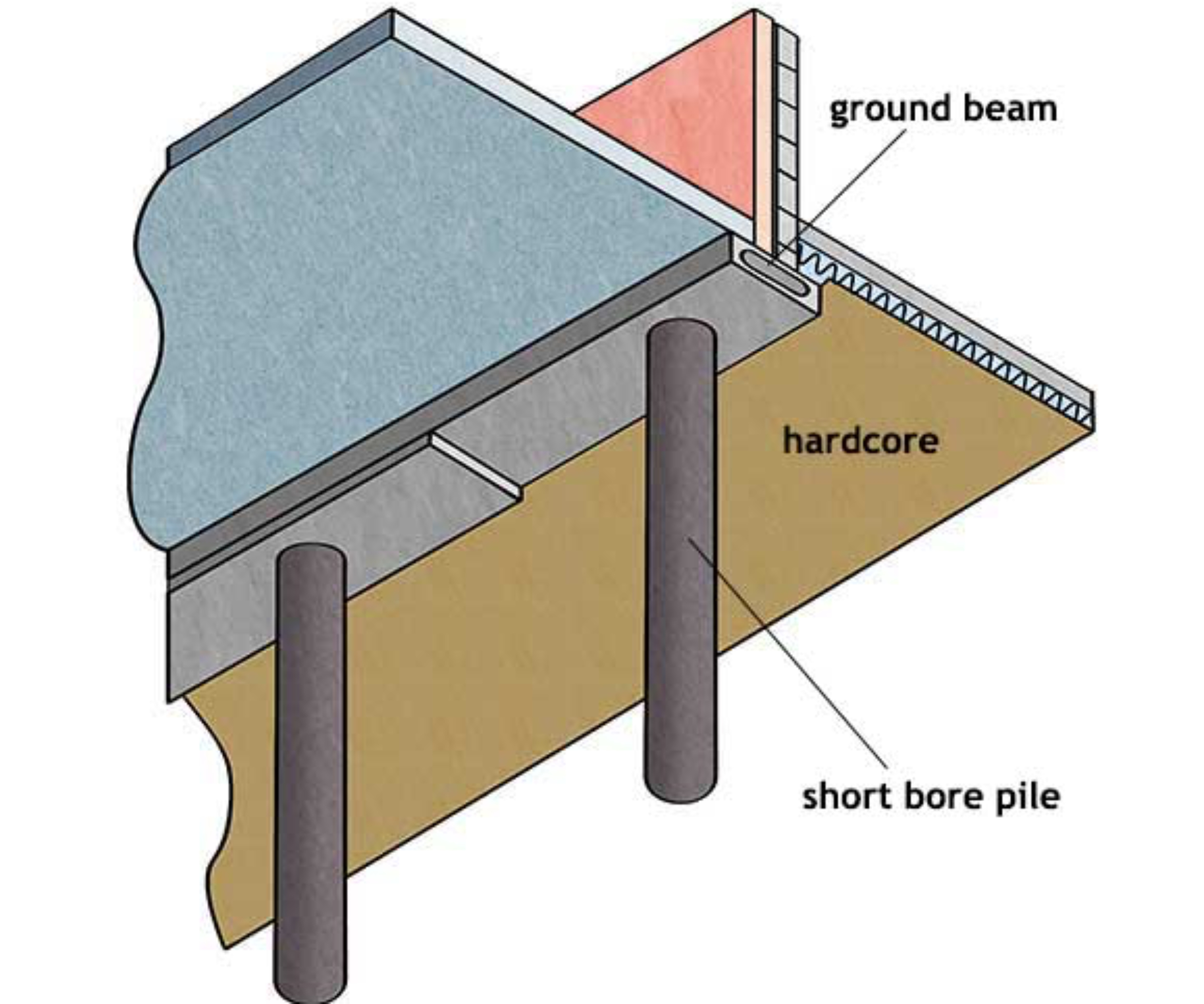

Piled foundations are concrete columns drilled deep into hard bedrock to securely anchor the building, aided by frictional resistance from the surrounding ground.

This method has become much more common in housebuilding since the advent of cheaper short-bored systems installed using hired mini-piling rigs. It’s now the most widely used foundation type after conventional trenches, thanks in no small measure to planning requirements encouraging retention of trees and the development of brownfield land.

Types of micro-pile systems

- Augered piling - widely used in clay subsoil and involves drilling holes (200mm to 600mm in diameter) as deep as 24m with an ‘auger’ (a rotating shaft with cutting blades). Once drilled, the auger is withdrawn and the hole filled with steel-reinforced concrete. This is the least expensive and most common method, and is virtually vibration free. On sites with very restricted access, lightweight hand auger tripods can drill with a diameter of up to 300mm and to a depth of 13m

- Continuous flight auger (CFA) piles - used in unstable or water-bearing ground. The main difference from augered piling is that the drilling pieces are hollow so concrete can be pumped directly to the bottom of the hole as the auger is withdrawn

- Driven piles - use a steel casing and are suitable for wet, unstable or contaminated ground. More economical than the CFA method, these piles come in sizes varying from 150mm to 320mm. The casing is first placed in a small pilot hole and then pushed into the ground using a suitable weight on a hydraulic pile driver. One benefit of this method is that it creates little or no spoil, saving on transport and disposal, thus also reducing the carbon footprint

- Screw piles (also known as helical piles) - akin to giant wood screws. These hollow tubular steel piles are wound into the ground by machine with no prior excavation. The main benefit is fast installation and minimal soil displacement and disposal.

Foundations for difficult soil

On ground with poor bearing capacity, such as soft sandy clays, the simplest solution is to dig down a little further. If a standard trench foundation is deep enough, its base should be supported on firm ground unaffected by seasonal changes, while beam and block floors can happily bridge across the surface.

In clay areas, however, the ground around the sides of the foundations will still be prone to periodic expansion and contraction as the ground becomes saturated and then dries. So to resist lateral pressure, the sides of the trenches can be lined with a flexible slip membrane which allows the clay alongside to independently shrink or swell.

Also, building wider foundations can help spread the load over a larger area, but this may require steel reinforcement to prevent shearing. And, as we have seen, with deeper trench foundations it soon becomes cheaper, easier and safer to switch to one of the following ‘engineered’ solutions.

"Unstable, or softer soil types, usually require relatively deep foundations, confirms Ninian, "again, steel or concrete piles are often the most suitable solution. These are prefabricated off site and then depending on the pile type (end bearing, friction, bored, driven, screwed) are installed at a depth where the more solid load bearing ground is located."

Pad foundations for difficult sites

Another type of system used when installing foundations for difficult soils is pad foundations.

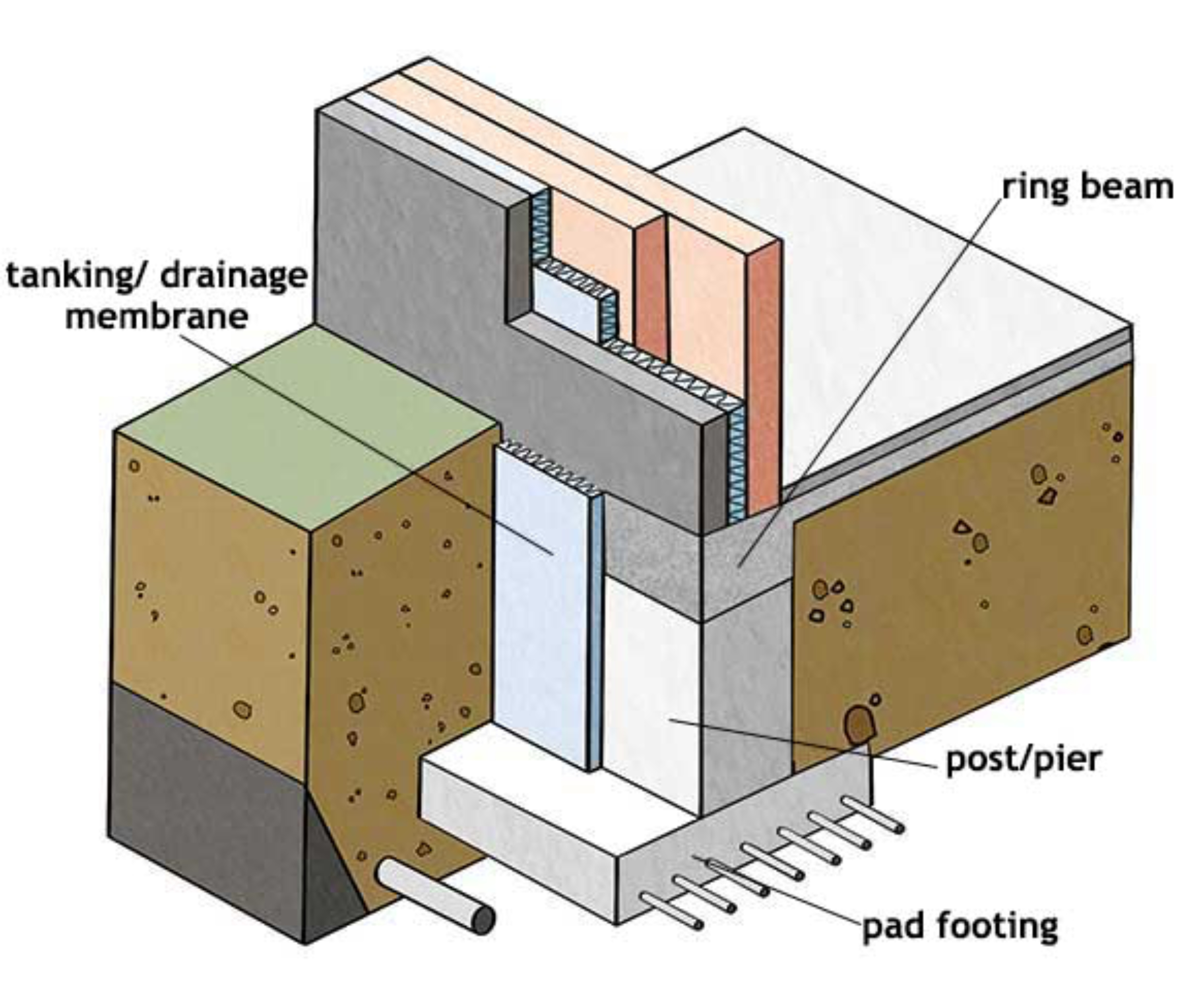

Pad foundations are designed to carry individual ‘point loads’. This type of foundation suits buildings with skeletal structures, such as steel frame or traditional post and beam, where the frame can be supported on a series of small concrete pads instead of the external wall sitting on continuous strips in the ground.

However, as with piled foundations, it’s possible to modify pads by constructing reinforced concrete ground beams that span between the concrete pads, making them suitable for supporting lightweight panel timber frame buildings.

Pads can also suit poor soils and can also be used to avoid problems where bored piling is sometimes obstructed by impenetrable pockets of rubble or hard gravel, snapping bits and jamming augurs. The downside is that the process is very labour-intensive.

On a positive front, one advantage of this system is that the construction process is within the capabilities of a competent self builder. Plus, it’s a reasonably eco-friendly foundation system as relatively small amounts of concrete are used.

The construction of pad foundations is also relatively straightforward.

- First a number of large holes are dug, about a metre deep. Typically these will be spaced quite close together at 600mm centres, and located at corners and under the more heavily loaded parts of the wall (for example, either side of window and door openings).

- Holes are normally dug by machine; a simple mechanical post hole borer can drill down to a depth of around 1.4m.

- Square or circular pads are cast individually in the bottom of each of the pits.

- Steel posts can then be bolted on top, or piers of brick or reinforced concrete built on to each pad foundation.

Foundations vs house type

Foundations for difficult sites will also need to be matched with your chosen method of house construction.

Masonry built homes

If you're building with masonry, conventional masonry walls are normally built on standard trench or raft foundations, since these readily provide a consistently level base.

Piled foundations are normally the most economical solution for sites where load bearing support is several metres below the surface, such as made up ground or shrinkable clay with deep-rooted vegetation. But where ground is unstable, a reinforced concrete raft that effectively ‘floats’ on the surface is a safer bet.

Timber frame structures

Modern panel timber frame structures are much lighter than those of masonry construction, so in theory should require less in the way of foundations. But as we have seen, what matters most isn’t so much the weight of house, but the fact that the load is bearing on firm ground that won’t move. As long as that box can be ticked, foundations shouldn’t be over-engineered for the loads they carry.

Another factor with timber frame walls – or indeed anything that arrives on site prefabricated – is the need for foundations to have a greater degree of accuracy (plus or minus 5mm) since there’s less scope to make up for errors on site.

However, pile foundation systems with ring beams can also be suitable for both timber frame and traditional masonry walls.

Pad foundations are suited to point loads from steel stanchions or post and beam walls but to prevent problems with damp and rot, traditional timber frame structures are probably best supported on short base walls built off ring beams.

Choosing the right foundations for difficult sites is key to keeping your timescales and your budgets on schedule. For more information and advice, read our guide to what you can expect to pay for foundations costs and equip yourself with the right questions when it comes to finding groundworkers with experience for your self-build project.

Chartered surveyor Ian Rock MRICS is a director is Rightsurvey.co.uk and the author of eight popular Haynes House Manuals, including the Home Extension Manual, the Self Build Manual and Period Property Manual.

Ian is also the founder of Zennor Consultants. In addition to providing house surveys, Zennor Consultants provide professional guidance on property refurbishment and maintenance as well as advising on the design and construction of home extensions and loft conversions, including planning and Building Regulations compliance.

Ian has recently added a 100m2 extension to his home; he designed and project managed the build and completed much of the interior fit-out on a DIY basis.

- Ninian MacQueenArchitect