What’s it like living with solar PV panels?

Energy expert David Hilton reveals his experience installing and using solar PV in his own home and reveals how he maximises the energy it generates

Living with solar PV panels isn't simply about installing them, it's a lifestyle. Solar PV (photovoltaic) panels are an eco-friendly addition to any home and they can make your home cheaper to run, but how you use solar PV will determine its real value.

Solar panels use sunlight to generate electricity, and while the Feed-in-Tariff – which offered homeowners with quite a generous incentive in the form of 46p/kWh electricity at its peak – is now closed, you can still export energy to energy companies. And with energy prices continuing to rise, solar PV is a great system to install if you have the right orientation and opportunity.

In my experience, simply installing solar PV is not enough. To fully benefit you’ll need to adapt your lifestyle to optimise the use of PV panels, and while they can deliver energy savings, do not expect to have zero bills and be aware that the yield (the amount of energy actually harvested from solar panels) in winter can be around 15% of the yield in summer.

Here’s my experience of installing solar PV panels and how it has impacted our home heating system.

When did I first consider installing solar PV panels?

I have always believed that if it seems too good to be true, it probably is. That was until the Feed-in-Tariff was introduced on 1 April 2010, which initially paid households 45p for every kilowatt hour (kWh) of electricity you generated from PV panels, while the cost of a kWh of electricity was 8p.

Suddenly everyone wanted a solar PV system and the awareness of renewables spread like wildfire. Fast forward a few years and the Feed-in-Tariff was no longer as generous and we learned it was closing to new applicants in 2019. Solar sales then dropped off a cliff.

Fortunately, that is not the end of the story. As the incentives and demand for PV fell, so did the cost of installations, but the payback on the investment would take a bit longer and was no longer based on incentive income alone.

So, as a family, we decided to explore whether we could fit the panels on our roof.

Why we needed planning permission for solar panels

Normally you would not need planning permission for solar panels as they are mostly fitted under Permitted Development rights (where they exist), but unfortunately for us our south facing roof faces the road, and together with the height of the road, we were excluded.

Solar PV installation cannot protrude more than 150mm above the plane of the roof and cannot protrude at all above the highest part of the roof. This meant that we had to have a conversation with the local authority planning department and eventually we got the green light to go ahead.

How we prepared for the solar PV installation

The first thing we had to do was measure the roof, then work out which way it faced and how many panels would fit on it. A reliable installer will be able to do this for you.

To work out which way your roof faces try to first find your home on Google Maps; the bottom of the page is south. Measure the angle from south in degrees, west is +90 (clockwise) and east is -90 (anticlockwise).

If your roof faces south then that is ideal because PV panels tend to work best facing south as they capture solar energy from dawn until dusk. But even if your roof faces east or west it still has a generation yield of 80% when compared with south.

Most solar PV panels measure around 1 meter along the short edge and between 1.6 and 2.3 meters along the long edge, depending on the output rating of the panel. Once you have measured the roof then you will be able to work out how many panels will fit on the roof.

Remember to allow around 300mm as a margin around the panels. You may need to use your geometry skills and Pythagoras Theorem (remember that?) to work out the ridge to gutter length.

The panels are the visible part of the installation but there is also a bit of equipment called an inverter, which converts the electricity that the panels generate (Direct Current) into the electricity that we use in the home (alternating current). The inverter is often installed in the loft or a garage and is roughly the same size as a square pillow.

Having done the measurement we could get 15 panels on the roof. These days the panels are higher capacity so you don’t really need more than around nine or 10. You may, however, want to allow more space if you are thinking about installing solar batteries at any time either now or in the future.

What was the cost of our solar panels?

A typical 4kWp solar PV system will cost anywhere between £5,500 and £9,000 for an on-roof system, and any additional framework will carry additional costs.

As our panels were installed 12 years ago the costs were very different - I also installed a lot of it myself which helped with costs. In those days the average system around 3.6kWp would have about 16 panels and cost around £12k - £15k fully installed.

You might be eligible for funding for solar panels on the Energy Company Obligation scheme, if you meet the eligibility criteria, but there's no denying solar panels can be expensive to install.

However, once installed you can benefit from the Smart Export Guarantee (SEG), which replaced the Feed-in-Tariff in 2020. Once your panels are installed, the SEG requires energy suppliers with 150,000+ customers to pay homeowners for any unused solar-generated electricity.

If you use around 60% of the generation (based on generating 3,700kWh per year) then you will save around £750 per year. Use more and the savings are better.

How do the PV panels work?

When all the solar equipment is installed it is wired back to your main consumer unit (distribution board). Any electrical equipment that is ‘on’ will automatically use the generated electricity first. This is the path of least resistance.

If you are generating 2kWh and the home is using 3kWh then you will use the 2kWh and draw 1kWh from the grid. If, however, you are generating 4kWh and only using 2kWh then you will be sending 2kWh back to the grid. Energy companies will buy this exported energy for anything between less than a penny per kWh to around 8p/kWh.

You can add an energy diverter that will switch on electrical circuits such as the immersion in your hot water cylinder when it detects that there is more energy being generated than you are using or you could add a battery system.

How has my home energy use changed?

When you first install a PV system you may not notice any difference but it is up to you to optimise the return on investment.

We do not have a solar battery yet but we have found that we run appliances such as the dishwasher, washing machine and tumble dryer during the sunshine hours. Don’t run them all at the same time as collectively they will draw more energy than you generate. Instead, set them to turn on one after another.

We found that whenever we replaced an appliance we opted for the WiFi-enabled models (yes, I know we all used to joke about apps for home appliances) but for these ones it empowers the ability to turn them off and on even when you are not at home (so long as they have been pre-loaded).

We also own an electric car, and with the addition of charging an electric car at home, things change. Depending on how many miles you clock up, and when you drive, you may need to juggle things around. I mostly drive during working days, therefore the appliances must run then.

We are now using our energy smarter

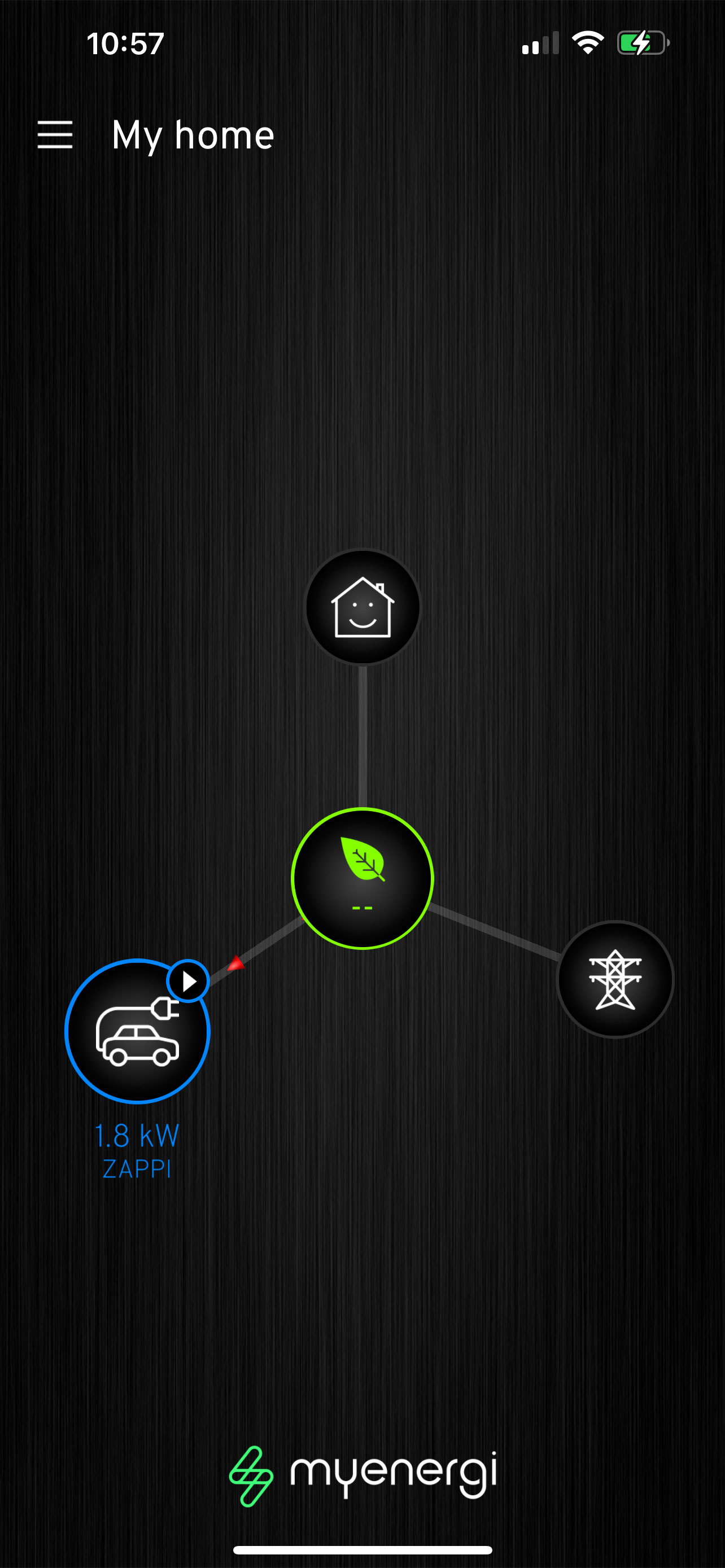

Since owning the EV I have installed a Zappi charger that has the function to only use excess generation from the PV. I leave the car plugged in over the weekend, and during this past weekend I was getting around 1.8kW to the car for around a total of four hours a day, which if you do the maths gives me an additional 50 miles of charge.

The weekend is for charging the car, lawnmower and batteries for power tools, then during the week the car is charged at night on an off-peak tariff. This does make the daytime tariff a bit more expensive so I am now looking at the battery option.

If you cycle the battery twice a day (maybe only once in deep winter) by charging it with the off peak tariff at night, use the charge for breakfast and morning energy, and then top it up with PV during the day so that you can use it in the peak evening times. This way you can optimise its payback.

The other thing to note here is to use a scalable battery system so you can start small, say with a 5kWh battery, and then if that is not enough you can add to it.

The payback on the Feed-in-Tariff alone took around 12 years. If you then factor in any electricity that you use yourself it drops the payback time to around 10 years. Given that the costs of installation have dropped and we are able to use more of our generation we have very similar payback times.

By adopting technologies and energy use management practices we can increase the optimal use of the generation and massively improve the payback time and return on investment.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

David is a renewables and ventilation installer, with over 35 years experience, and is a long-standing contributor to Homebuilding and Renovating magazine. He is a member of the Gas Safe Register, has a Masters degree in Sustainable Architecture, and is an authority in sustainable building and energy efficiency, with extensive knowledge in building fabrics, heat recovery ventilation, renewables, and also conventional heating systems. He is also a speaker at the Homebuilding & Renovating Show.

Passionate about healthy, efficient homes, he is director of Heat and Energy Ltd. He works with architects, builders, self builders and renovators, and designs and project manages the installation of ventilation and heating systems to achieve the most energy efficient and cost effective outcome for every home.