Delist a Listed Building: Here's How and Why I Did It

Choosing to delist a listed building is a big step but hugely beneficial. Homebuilding's Amy Willis explains how to apply, the cost and her tips for success

Applying to delist a listed building is an option for those with period properties that have lost their historical significance.

Older homes are vulnerable to decay and when a listed building is beyond restoring, or it no longer retains enough of its original fabric to be worthwhile preserving, it can become a good candidate for delisting.

Historic England estimates that there are around half a million privately-owned listed buildings in the UK, which are compiled on Historic England's listed buildings register. Surprisingly, Historic England is unable to put an exact figure on how many listed buildings are on the register. This is because one entry might include a number of individual buildings, for example a row of terraced houses.

That said, around 91.7% of buildings on the register are Grade II listed and owned by private homeowners, with the other two types of listed building being Grade I and Grade II*. The sheer volume of privately-owned listed properties means it is down to homeowners to notify Historic England if their property should be delisted.

In our guide on how to delist a listed building, I explain how I delisted my Grade II listed home and if your home might also be a good candidate for removal from the register too.

Why Apply to Delist a Listed Building?

While Historic England's listed buildings register seeks to protect historic material, it can also inadvertently protect any aspect of a listed building, including modern additions.

This can be frustrating during a renovation, especially in a build that is listed yet lacks much of its original fabric.

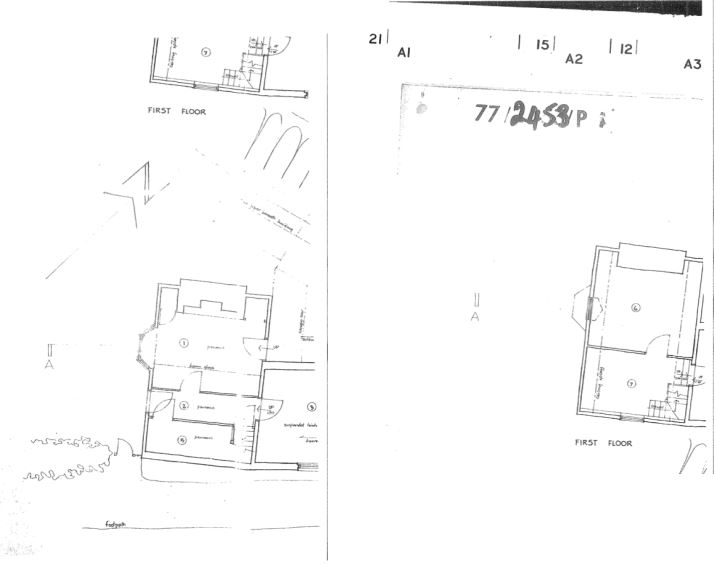

While renovating my home, I encountered this exact scenario. The Grade II listed cottage came with a damaged '70s glazed front door on a modern red brick extension. Yet despite the door being installed in the 1970s, it still took six months to secure listed building consent to replace the door. This required existing and proposed elevation drawings, a site plan, a location plan, a design and access statement, a heritage assessment and photographs among other details.

The reason for this is the system has to base itself on the assumption that everything about a listed building is historical. It's then up to your local council's conservation officers to assess the information before making a decision. And the only way conservation officers can accurately do this is by requiring detailed plans for any changes.

But what if a listed building no longer has enough of its original features to warrant inclusion on the list? In many cases, buildings were added to the register decades ago without ever having their interiors inspected. These are known colloquially as "drive-by" listings, where experts literally drove around the country listing buildings from the outside if they looked like they were important.

This worked in the majority of cases, but it also meant some historic buildings were missed from the register (usually the ones down smaller roads) and some were added to the register despite original features already having been lost, usually long before the listing and grading process existed.

Other cases where a home might be worth reassessing, include where a listed building has been rebuilt. This might be due to fires, flooding and other disasters where historical features are damaged beyond being salvageable.

Is My Listed Building a Good Candidate to Delist?

The criteria for inclusion on the listed building register is whether the property holds "special architectural" or "historic interest". If your property no longer meets this criteria, you could potentially have a good case to delist your home.

"The older a building is, and the fewer the surviving examples of its kind, the more likely it is to be listed," it says in Historic England's criteria.

Understanding your property, is a good place to start. For instance, if your house is a timber-frame property from the 1800s yet sits on a brick plinth with cement mortar and a damp proof course, this might be good evidence that the structure has undergone a rebuild.

This was the case with my listed cottage and it prompted me to conduct further explorations. Digging down beside the exterior of the house revealed one-metre deep concrete foundations. Cement render covered the exterior too – identified by making an exploratory hole – and the chimney stack had been rebuilt with a modern chimney pot.

Internally, clues included walls that were missing timber beams, concrete and gypsum plaster, plasterboard and fiberglass insulation. Straight timber beams with machine marks also indicate non-original features as timber homes of this era would have been more than likely built with hand-cut timber. Often it was recycled timber too.

Pulling up carpets was also important to see if there was any original flooring or floor structure. In my home's case, this was long gone, replaced by more concrete.

It is also worth having a look at any historical planning documentation for your home. This isn't always available online and might be held on a micro-fiche at your local council's offices. But it's worth investigating because planning documents can provide evidence of where original features have been removed.

In my property's case, planning documents showed the layout of the house had undergone a complete overhaul. All the original windows had been replaced, walls had been demolished, exterior door openings had been moved and the original staircase had also gone.

Essentially, the property was a "drive-by" listing where much of its original fabric had already been lost but the experts hadn't been inside the house to assess it.

A loss of significant original features still might not be enough however, if your home is unique. My listed building was a farm worker's cottage with many other examples of the building type in the area. If it had been a home to a member of the aristocracy or someone of historical importance, it is unlikely to have been a good candidate for delisting.

The full listed building criteria is set out in the Government's Principles of Selection for Listed Buildings. This is important reading for anyone considering delisting.

How to Remove a Listed Building From the Register

If you believe there is strong evidence to support an application to delist your listed building, you will need to complete an online form called the Listing and Designation Application Form on Historic England's website.

Historic England will review your application and if accepted, a listings adviser will be assigned to examine your property. The adviser will inspect the property to see how many original features still exist and take photographic evidence of their findings.

They will also photograph and note where original features are missing.

Once the adviser has inspected the property she or he will write-up a consultation report. Once complete, this is sent to the applicant to comment and add their own observations within 21 days.

One of the observations I made, was to clarify some of the wording. Where the listing adviser had described an 'oak ledged door' leading into the living room, I made sure I clarified that the oak door was not original as I had installed it myself a few weeks earlier.

Once you have sent your comments back to Historic England's listing adviser, there is a consultation period within Historic England. After this, Historic England will make their recommendation to the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). This recommendation will either be for the listed building to remain on the register or for it to be deleted. If it is deleted, it will have been successfully delisted.

It is worth noting that if your listed building is recommended to remain on the register, it is possible for the description of your listed building to be updated based on the internal inspection.

Historic England have a thorough guide on removing a listed building from the register that is worth reading in full.

When Delisting a Listed Building is Unlikely

Historic England state that if you are awaiting a response regarding listed building consent, your application to delist is unlikely to be considered. The same applies if any enforcement action is being taken or listed building consent has been refused and you are appealing that decision.

When delisting a listed building after fire damage, Historic England will not consider an application to delist until the cause of the fire has been established and any enforcement action has been ruled out.

Other instances where Historic England state they will not look at delisting a building include: where urgent works notices have been served, compulsory purchase procedures or where repairs notices have been given.

For this reason, only apply to delist if the above does not apply. More information on this can be found in Historic England's delisting guide.

Timescales: How Long Will My Application Take?

If you are delisting your property through the free route, the timescale can be anything from four months to over a year. It completely depends on Historic England's workload. If you chose the fast-track system, then this will be reduced to three months.

When delisting my own listed cottage, the entire process took a year and five months. This was from initially filling out the online application form to a decision to delete from the register being given by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. However, this was during the pandemic and the application wasn't picked up properly until five months after the application was submitted.

If you need it to be faster, you can submit a paid application instead on Historic England's fast-track system. This should guarantee Historic England's recommendation is made to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport within 12 weeks.

How Much Will It Cost to Delist My Listed Building?

The application is free of charge if you are not using the fast-track route.

If you choose to fast-track the process will cost between £2,000 and £6,000. Historic England says the average cost is around £3,000 but it varies depending on the complexity of the case and how much time it takes to consider.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

Amy spent over a decade in London editing and writing for The Daily Telegraph, MailOnline, and Metro.co.uk before moving to East Anglia where she began renovating a period property in rural Suffolk. During this time she also did some TV work at ITV Anglia and CBS as well as freelancing for Yahoo, AOL, ESPN and The Mirror. When the pandemic hit she switched to full-time building work on her renovation and spent nearly two years focusing solely on that. She's taken a hands-on DIY approach to the project, knocking down walls, restoring oak beams and laying slabs with the help of family members to save costs. She has largely focused on using natural materials, such as limestone, oak and sisal carpet, to put character back into the property that was largely removed during the eighties. The project has extended into the garden too, with the cottage's exterior completely re-landscaped with a digger and a new driveway added. She has dealt with de-listing a property as well as handling land disputes and conveyancing administration.