How do solar panels work?

Asking 'how do solar panels work?' is a great first step in increasing your home's eco credentials and deciding which types will be right for you

There could not be a better time to start asking 'how do solar panels work?' and 'how can they help me save money?'.

Whether it’s a photovoltaic (PV) system of 3.5kWp maximum power output or a solar thermal system that produces 1,800kWh to 2,000kWh (depending on type – see below) per year for 25 years – both of these will provide you with power for a unit cost of a little over 6p/kWh. Compare those figures to what you are currently paying for gas and electricity and you will see why solar power is a good idea.

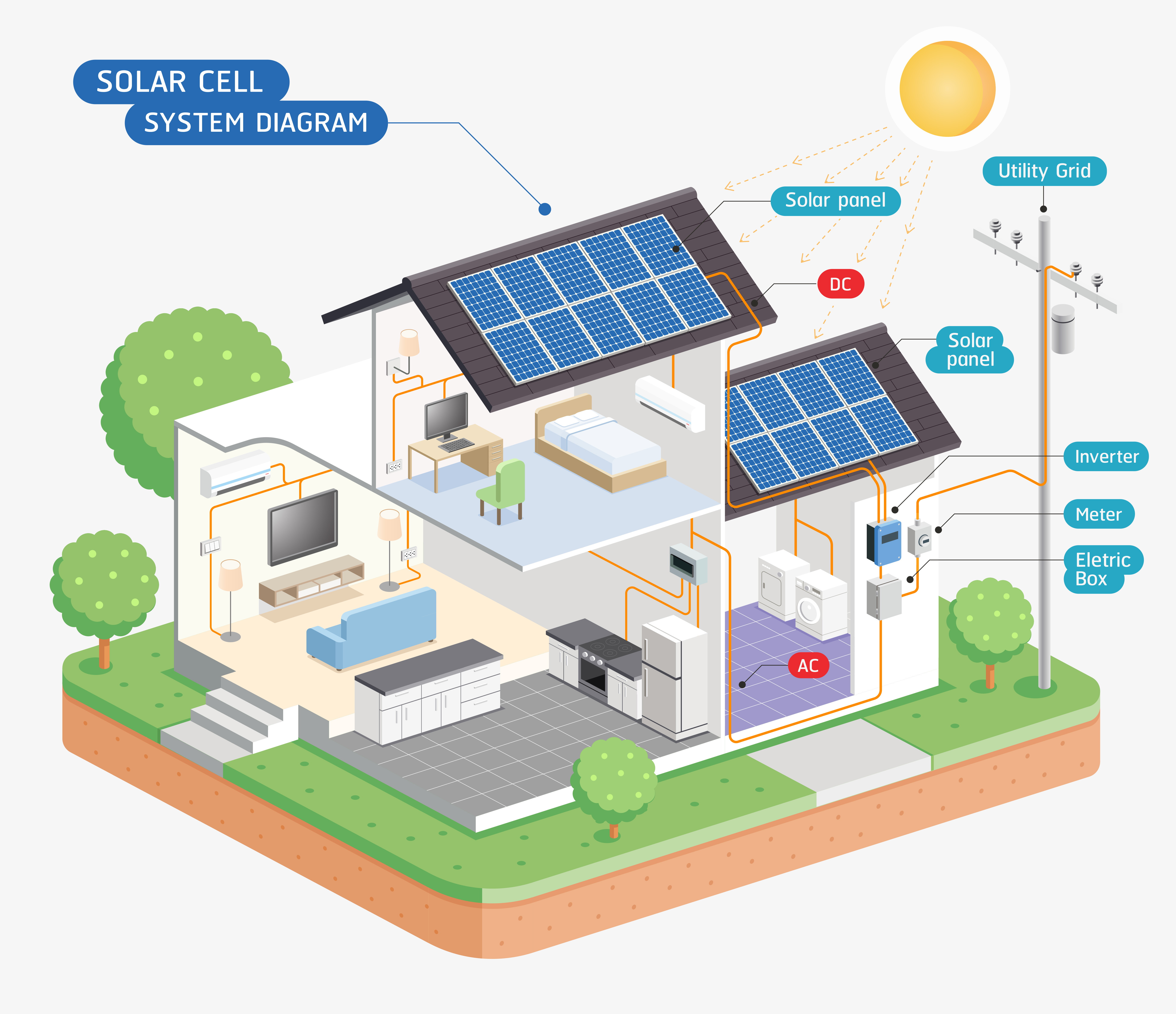

Below, find a step-by-step guide to the workings of both solar PV and thermal systems, how they might be able to work for your home and answer the most commonly asked questions around how solar panels work.

How do solar panels work: A step-by-step guide

A solar PV system is made up of a number of panels varying with the size of the array. Each panel has a number of cells (varying with the size of panel). It is these cells that do all the work.

Put simply, here are the physics involved in a PV cell:

- Sunlight hits the negative silicon layer, exciting the electrons therein

- Those electrons then move through the interface to the positive silicon layer below

- This creates an electrical flow

- Contact strips top and bottom collect that electricity and carry it away to the home

- The amount of electricity produced is a factor of the level of excitement in the electrons, which is a factor of the intensity of the sunlight.

What are solar panels made from?

The cell broadly consists of two layers of silicon crystal – one positive, the other negative – with various things like interface layers and boron layers to make it all work and improve efficiency.

Do solar panels give you free electricity?

Due to the significant cost outlay together with maintenance costs the electricity produced by installing solar panels cannot be considered free. However, it is very cheap compared to electricity supply prices.

Now that the government subsidy, in the form of the Feed-in Tariff, is no longer available, the best way to make the system stack-up financially is to also install a solar battery storage system because the PV array produces all its power during the day whereas we want power mostly in the evening.

That means that around 60% of the power produced during the day is shipped out to the grid, for which we are paid around 5p/kWh (although that is rising with some electricity suppliers due to the current energy crisis). We buy back electricity at around 20p/kWh. It costs nearly 6p/kWh to produce electricity so if we sell it to the grid we will take a loss. If we install a battery system we can use all the electricity produced in the house and offset the 20p/kWh bills.

The alternative is to use excess electricity to heat water. There are a few systems available, like the Immersun or Solar iBoost. These systems divert and control the electricity generated to an immersion heater in the hot water cylinder, thereby offsetting gas bills. With gas at 7p/kWh we are still making a profit, albeit fairly small. And it is not clear that gas will still be available in 25 years time.

How do solar thermal panels work? Step-by-step guide

Solar thermal panels produce heat, not electricity. And on sunny days they can produce serious amounts of heat, enough to heat and fill a 200-litre tank in under an hour. Solar thermal systems come in various forms:

Flat plate

As the name suggests flat plate systems are a rectangular box with a usually toughened glass top layer.

- Sunlight passing through the glass (or other transparent material) cover creates the greenhouse effect generating heat

- A black coated copper or aluminium plate absorbs the heat

- Copper pipes containing a water/glycol mix collect the heat

- Other pipework conveys the heat to a hot water cylinder

- Insulation helps prevent that heat escaping.

A system will comprise one or more panels, a control system to turn the pumps on when there is heat to be collected and off when there is not, pumps and a hot water cylinder.

An array would often be two panels, which has the potential to collect a lot of heat on a sunny day. Therefore a large hot water cylinder would be useful. A 300-litre cylinder would not be uncommon. A thermal store would also be a good idea as in winter it may have to store that hot water for a few days, waiting for the sun to shine again.

Evacuated tube

Evacuated tube systems can collect more sunlight than a flat plate panel but it is also more expensive. Apart from the evacuated tubes, the system as a whole is the same as for flat plate.

An evacuated tube comprises:

- An outer glass tube, the diameter of which will vary with the manufacturer

- An inner tube, being the heat collector

- A water/glycol mix pumped through the inner tube to carry the heat away

- A vacuum ensuring the heat generated is retained in the tube.

- A header manifold to collect the heated water/glycol mix and carry it away.

The number of tubes in a set can vary, as can the diameter of the tubes, which can range from 50mm to 110mm though both are similar in efficiency. A good installer is more important than the diameter of the tubes being installed.

How long do solar panels last?

Solar PV cells tend to not fail but the inverter can, as can the electrical connection panel-to-panel. And repair can be run to four figures. The best advice is to check the warranty. Many installers offer a 25-year guarantee on the panels, which are extremely unlikely to break down. Others offer a 25-year guarantee on power production (essentially the same thing as guarantee on the panels) and not really in question. The best comprehensive guarantee tends to be 10 years.

A solar thermal array is more robust although evacuated tube systems can be susceptible to impact. Replacing even one tube could cost £1,000. Anything else that might fail – control system or pumps – is readily accessible and relatively low cost.

Can you run a whole house on solar panels?

You can run a whole house using solar panels, but not easily. The majority of the electricity demand is in the winter, when the sun does not shine much. So we have to calculate the daily demand for electricity in the winter when working out the size of solar array needed. The typical solar array is 3.5kWp to 4.0kWp which will take up 20m2 30m2. Such a system is likely to produce around 3kWh per day in winter when we might be needing 20kWh per day. To meet that demand we would need an array of 28kWp which would take up 140m2 and produce far more electricity in the summer than could be dealt with.

If you want to run the house on renewable electricity produced on site, mixing technologies, such as solar and wind, is usually the answer. Hybrid solar panels (also known as solar PVT) are also an option for those who desire both electricity and hot water generation.

Does bad weather affect solar panels and do solar panels work at night?

Bad weather will impact production to varying degrees, depending on how bad it is. Modern solar panels are designed to work on cloudy and rainy days, but you'll find best results on clean, sunny ones.

Solar panels do not work at night as they function using sunlight.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

Tim is an expert in sustainable building methods and energy efficiency in residential homes and writes on the subject for magazines and national newspapers. He is the author of The Sustainable Building Bible, Simply Sustainable Homes and Anaerobic Digestion - Making Biogas - Making Energy: The Earthscan Expert Guide.

His interest in renewable energy and sustainability was first inspired by visits to the Royal Festival Hall heat pump and the Edmonton heat-from-waste projects. In 1979

this initial burst of enthusiasm lead to him trying (and failing) to build a biogas digester to convert pig manure into fuel, at a Kent oast-house, his first conversion project.

Moving in 2002 to a small-holding in South Wales, providing as it did access to a wider range of natural resources, fanned his enthusiasm for sustainability. He went on to install renewable technology at the property, including biomass boiler and wind turbine.

He formally ran energy efficiency consultancy WeatherWorks and was a speaker and expert at the Homebuilding & Renovating Shows across the country.