A Guide to Chimneys

Whether you are self building or renovating, if your property has a chimney you’re going to want to ensure that it is in the best working order

Chimney systems not only add a great sense of character to a home, but are also essential if you plan on enjoying the cosy benefits of a woodburning stove. This guide will explain all you need to know about chimneys and flues and how to make sure yours is working to its full potential.

Why do We Have Chimneys?

Although holes in the roof and walls of ancient homes is evidence that our ancestors knew it was important to get smoke out of their homes, chimneys were not really widely adopted until the Tudor times, and even then, only by the upper classes, with more common folk having to put up with smoke-filled rooms.

Even when chimneys were used, they were highly inefficient and often dangerous too, being made of wattle and daub and susceptible to fire. By 1710, all clay-built chimneys in England were ordered to be rebuilt in brick.

However, a poor understanding of heat and smoke meant that chimneys were still not drawing in the way they should, and it was not really until the mid-18th century when the likes of Benjamin Franklin (once called ‘The Universal Smoke Doctor’), Charles Willson Peale and Benjamin Thompson – later known as Count Rumford – got involved that things improved.

Count Rumford invented a fireplace and chimney designed to reduce the smoke pollution in London. The new Rumford fireplace reflected heat back into the roof, with the chimney being incorporated into the wall.

How do Chimneys Work?

Jonathon Greenall from Clearview Stoves, says, “You can run a bad stove on a good chimney but not a good stove on a bad chimney. That’s how important it is that a chimney works properly. First, you need to know what makes a chimney do its job. In other words, why does the smoke go up the chimney rather than drift out into the room?”

The upward movement of air and smoke in a chimney is known as the draft. Draft takes place because of the physical fact that hot gases are less dense than cold gases. Heated gases in a chimney are lighter than the air in the atmosphere and are, therefore, drawn up into it.

Logic suggests that a taller chimney produces more draft because of the simple fact that there tends to be more of this hotter, lighter gas in it, which creates more updraft. However, the increased draft inherent to a taller chimney tends to be offset by the greater friction found in the chimney and by the tendency of the gases to lose their heat as they rise.

A very dirty, roughly-lined, tall chimney, subject to poor insulation and possible air leaks could well be less efficient than a well-designed shorter chimney.

Another fact of physics has an impact – albeit a lesser impact – on chimney performance. As air is blown over the end of a tube, a drop in pressure is created at the end of the tube. This principle was first discovered by an Italian, GB Venturi, almost 200 years ago and is the principle by which most carburettors inject petrol into the air stream. Wind blowing over a chimney has a similar effect, adding to draft.

For a chimney to work well, it requires a good flow of air and for the flue to maintain as high a temperature as possible, so there are exacting Building Regulations about chimney design. For instance, it’s important for chimneys to be insulated, as this keeps the smoke warm and lessens the chances of it condensing as tar deposits. This is particularly important with woodburning appliances, as they burn cooler than coal.

Chimney Terms Explained

- Flue: The void through which the products of combustion are removed into the atmosphere

- Flue liner: The material used to form the flue within the chimney

- Flue pipe: A metal pipe used to connect an appliance to the flue

- Chimney: The structure surrounding one or more flues

- Chimney terminal: Another word for pot, cowl or other method of finishing off the top of the chimney

Types of Flue

The terms ‘flue’ and ‘chimney’ are often confused. The flue is the working section of the chimney which takes the products of combustion up and out into the atmosphere, while the chimney is a structure built around a core of clay or concrete flue liners, terminating with a pot (see Anatomy of a Chimney below).

Chimneys are categorised into ‘classes’.

- A Class 1 chimney is common in houses built up until the 1960s. They consist of a brick-built stack, situated on either an internal or external wall and containing multiple flues for multiple fires (although the fires cannot share a flue). This type of chimney can be used with all types of solid fuel fires and stoves, and gas fires too. They will need lining only if they fail a smoke test

- Class 2 (5” diameter) gas flue systems are often found in houses built from the 1960s onwards. They consist of an interlocking metal pipe running through the house, but can be used with certain types of gas fire only. Class 2 (pre-cast) systems consist of a rectangular hollow cavity made from concrete or clay blocks, travelling up the wall cavity to a ridge vent or metal flue terminal on the roof. They can be used with slimline gas fires

- Balanced Flues: A balanced flue exits from the back of a gas fire and obtains its air for burning from the outside and in turn expels the products of combustion through the same flue

- Fanned flues look similar in appearance to balanced flues but take their air for burning from the room in which they are installed. Electrically powered, they can be located away from an external wall. Both options are a good choice where there is no useable chimney

Chimney Materials

Both chimneys and flues are available in a variety of materials, including stainless steel, concrete, pumice, clay or ceramic, and plastic. Concrete, pumice and clay or ceramic are collectively known as ‘masonry chimneys’.

Plastic flues can only be used with low-temperature condensing appliances, and some stainless steel chimney systems and liners are designed only for use with gas-fired appliances. Clay and pumice chimney systems however are suitable for use with wood, multi-fuel, oil and gas appliances.

Factory-produced pumice, clay and ceramic chimney systems can be retrofitted, but they tend to be reserved for new builds as they require foundations and their construction is really best left to a skilled bricklayer.

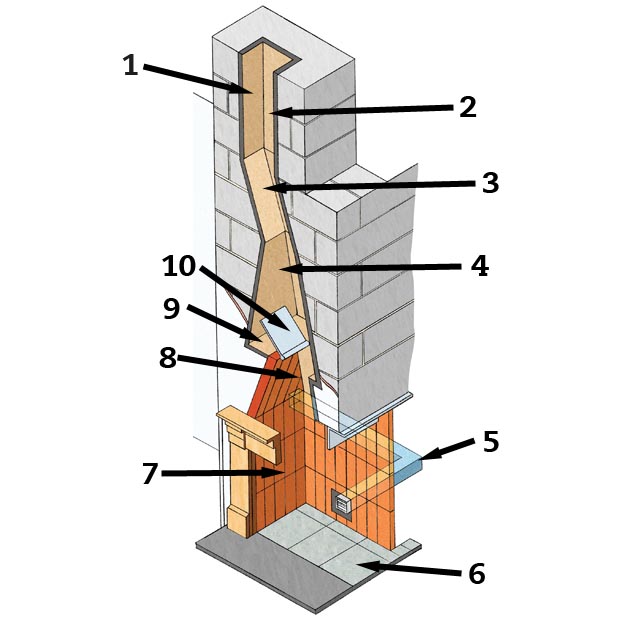

The Anatomy of a Chimney

NB: The diagram below dissects a masonry chimney with one flue. A chimney may in fact contain more than one flue, and its type is dictated by the heat-producing appliance required. To open up an old chimney, the flue must be cleaned and inspected by a professional chimney sweep, and possibly relined to meet regulations.

- FLUE LINING: An approved fire-resistant material which lines the inside of the flue, usually made of refractory concrete or impervious clay, but sometimes metal. All chimneys have to be built with a flue lining to protect the masonry from combustion gases, of which the lining also improves the flow. It was not uncommon for old flues to be pargeted (lined) with lime mortar as the chimney was erected, but many were not lined at all. There are two types of liner: Class 1 (solid fuel) and Class 2 (gas).

- FLUE: A vertical pipe or duct that provides a safe pathway for heat, smoke and other combustion byproducts away from the fireplace. Lies within the interior of the chimney. Flues must be high enough to ensure sufficient draught — around 4.5m in most cases.

- FLUE CONNECTOR: Connects the fireplace to the flue. Bends shouldn’t exceed 45°, to enable them to be swept clean.

- SMOKE CHAMBER: The space directly above the damper, where the smoke ‘gathers’ before passing into the flue.

- COMBUSTION AIR INLET: The fire must be supplied with air from outside the home in order to safely burn fuel; this inlet controls the quantity of the air supplied for combustion.

- HEARTH: A base that isolates a heat-producing appliance from people and combustible items. The hearth’s thickness is dependent upon the appliance.

- FIREBRICK: Laid masonry of refractory brick forming the rear and side walls of a fireplace. Refractory bricks are made of a ceramic material built primarily to withstand high temperatures.

- GATHER: A narrow opening between the outlet of the fireplace and flue, over which a damper is usually situated, to improve draught and reduce pressure in the smoke chamber.

- SMOKE SHELF: A horizontal surface directly behind the damper of a fireplace to prevent downdraughts. It also helps the chimney draw the smoke up into the flue.

- DAMPER: Also called a ‘throat’. A pivoted or sliding metal flap in the flue that regulates the amount of draught, preventing excessive variations. It can also close off the fireplace from the outside of the house, preventing air loss when the fireplace is not in use. Sometimes it is located on the appliance.

The Importance of Ratio

For an open fireplace to function properly and for the chimney to draw, the ratio between the chimney and fireplace needs to be exactly right. Flues above 6m tall should generally be not less than 1/7th to 1/8th of the area of the fireplace opening, e.g. a 225 mm (9″) diameter flue will support a fireplace opening up to about 550 x 550 mm (22″ x 22″) (see Building Regulations J 2.2.)

For bungalows, the ratio should be reduced to 1/6th.

A major advantage of precast fire chest and chimney flue systems is that the ratios have been carefully worked out and so are guaranteed to function properly.

If you are building a new chimney, take note at what works for the surrounding properties. They will already have been built or adapted for the local environment.

When fitting a liner, joints should have their male spigots facing down. The idea is not to make sure all the smoke goes up it will if joints are properly sealed but that water running down gets right to the bottom where it will be boiled away again.

How Much Will it Cost?

Material costs for a new chimney start at around £1,000 and can spiral upwards depending on the design. However, there is generally a considerable labour element.

The budget option with a woodburning stove is a prefabricated stainless-steel flue. Whereas a gas-burning appliance can use a single-skin flue, with solid fuel you have to use an insulated twin-wall flue section in order to stop the smoke condensing inside the flue. Typical material costs for a 7m twin-wall stainless-steel flue are around £1,300-£1,500. Main manufacturers are Rite-Vent, Poujoulat, and SFL.

Ceramic twin-wall flues are a more upmarket option, and are 30-50% more expensive than stainless steel. Ceramic flues tend to come with a 30-year guarantee (rather than ten years for stainless-steel flues). They’re recommended for heavy use, especially with biomass boilers.

Pumice stone prefabricated flues provide a very simple way of building a long-lasting, insulated masonry chimney system, at a similar cost to a twin-walled stainless-steel flue. Instead of having to source components from several different suppliers, these chimney systems are supplied as kits for easy assembly. Names to look out for here are Isokern and Anki.

In short, chimneys require foundations while steel or ceramic flues don’t. If you want a traditional pot, then you need a chimney, as flues have terminals instead. While flues work with any construction type, chimneys work best with blockwork.

Maintenance

The main cause of smoke coming into the room from an existing chimney that once worked is a blocked flue. The solution is to get the chimney swept. Insufficient air coming into the room can also cause blow-back. Bear in mind that, traditionally, houses had lots of draughts while today they are often too airtight for an open fire.

If you don’t give the fire sufficient oxygen, it will find its own, pulling great gulps of air down the chimney and belching smoke out into the room. If necessary, add a vent to an outside wall adjacent to your stove or fireplace.

Renovating Existing Chimneys

Many people will want to keep an existing chimney and adapt it for use with a woodburning appliance. You need to check that the chimney is functional and adequate — a chimney sweep should be able to help here.

And it is now commonplace to install flexible flue liners, usually pushing them down the existing chimney. Whilst often not essential, a flexible flue liner will help with the free flow of smoke and make for a more efficient chimney. Expect to pay between £400 and £600 for flexible flue liners, plus the labour to fit. Bear in mind there may be a lot more work you need to undertake to bring an existing chimney back into use.

Gas Fires

Most gas fires can be installed using a through-the-wall balanced flue, just like a gas boiler. You can also used powered flues, which allow you to duct the exhaust gas over longer routes incorporating bends. This enables you to place a gas fire away from a suitable external wall.

Thanks to Jonathon Greenall and Helen Davis at Clearview Stoves for their practical advice regarding flues.

Get the Homebuilding & Renovating Newsletter

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.